Dan Scott is the sort of retiree whose resting state might be more active than men half his age.

He’s 66, but that’s just a number. The arbors, trellises and that custom platform supporting 19-foot-tall cherry tomato plants are a testament to a man who never really quit work.

Not your average backyard plot, but Dan’s not your average guy.

He spent 37 years at The Korte Company. For 36 of those years, he was a construction superintendent.

Some of the toughest, biggest builds we’ve ever delivered were successful because of him, and it’s easy to see why. To Dan, work wasn’t “work.” Construction projects were symphonies. He was the conductor.

A knack for building

Dan “always had a knack” for building. Every job he ever had was related to construction.

First, the Highland, Illinois-native was an assistant to the man who kept time for construction workers stationed at a coal mine in nearby Albers.

Then, he worked for Aviston Lumber. After that, it was Community Builders in Highland. He recalls being the lone man responsible for setting and then removing the oiled plywood forms used to pour foundations.

Later, he worked for Host Homes. The industry was slow in the late 1970s. Most of his work was roofing, hauling 80-pound bundles of shingles up a ladder day after day.

“You worked hard,” Dan said. “It was a long, hard day.”

Then, the local carpenters union approached Host with a deal. They needed more warm bodies, so they relaxed the rules. Based on Dan’s past experience, he was labeled as a journeyman then and there.

All he needed to do was confine his work to residential projects for two years before going commercial. He didn’t have to go through apprenticeship school.

This is what led him to The Korte Company. Once his two years were up, he heard the company was looking for carpenters. He didn’t know it at the time, but he had a pretty good in with founder Ralph Korte.

That’s because Dan’s grandfather was Victor Wick, a well-known local cabinet maker and a man who knew hard work. Ralph knew all about work, too. And he knew Victor Wick, whose reputation as a “very particular” craftsman outlived him.

So when Dan approached Ralph about that job, Ralph was blunt: “I don’t know you,” he said. “But I know your grandfather. If you can work like he does, you’ll do fine.”

Work. In places like Highland in those days, work ethic was capital, worth more than its weight in gold.

“Everybody worked hard,” Dan recalled. “Especially around Highland, they were all farmers.”

Some of them were aspiring rock stars, too.

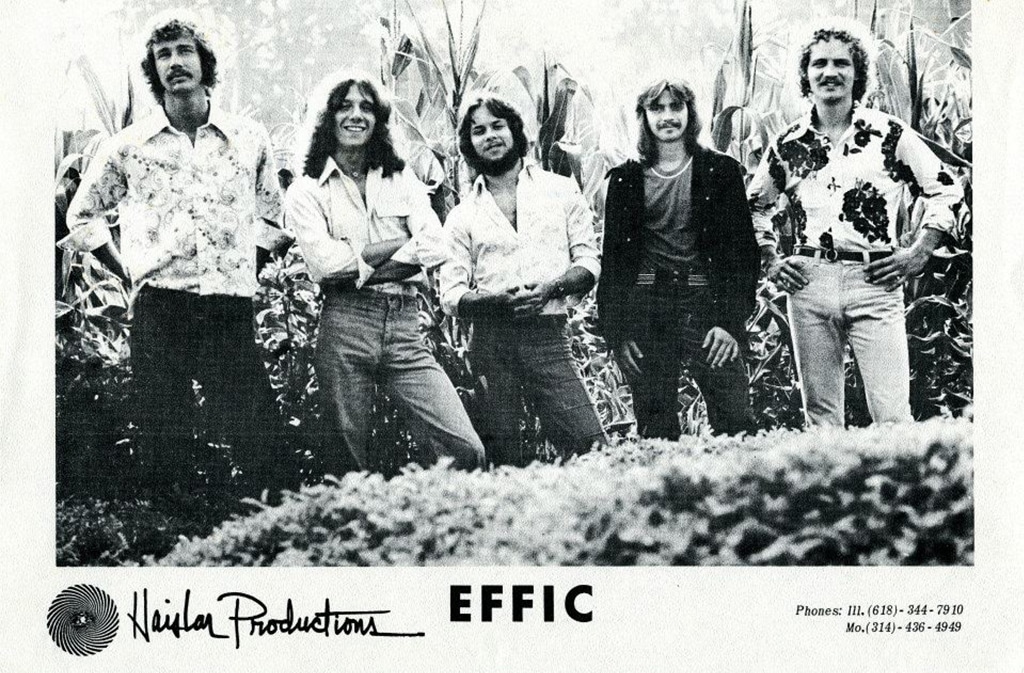

Effic: Rock ‘n roll, bomb scares and a foggy night in Carbondale

“Effic” is not a typo. It’s the name of a regionally famous rock band founded in the waning days of 1970. And for five years, the band’s guitarist was Dan Scott.

The truth of how the band got its name is probably lost in the reverb, but Dan thinks “Effic” refers to a discussion the bandmates had one night.

“It had to do with one of us asking, ‘What would be the effect of our music?’” he said. “And I think someone was eating a piece of cake. ‘Effect’ came out sounding like ‘effic.’”

How Dan came to join the band is a funny story, too. Effic’s drummer didn’t have any drums, but Dan’s brother had a drum kit. Asking Dan to join as a guitarist gave the group access to the drums.

Effic hustled throughout the early 1970s. At their peak, they played six nights a week, employed a squadron of roadies and bumped around the Midwest in an old blue bus that prominently displayed the band’s mascot. ‘Ajax’ the duck wore a cape and low top All Stars.

The marginally roadworthy bus could be seen all over the St. Louis area and also made regular stops as far away as Cedar Rapids, Iowa; St. Joseph, Missouri; Vincennes, Indiana and Chicago.

As you can imagine, Dan has some stories.

Notably, Effic was forced off-stage not once but twice due to bomb scares, which were quite common in the U.S. at the time.

One of those happened in Bloomington, Illinois. Effic was the top-billed band that night but they never played a note. The other was much closer to home, in Godfrey, Illinois. “They were in such a hurry about evacuating that we couldn’t even put our instruments away,” Dan said.

Then there was the night the bus broke down between Carbondale and Marion, Illinois. Socked in by heavy fog, the band flipped on the hazard lights as they searched in vain for the problem.

Every motorist who came across them stopped, confusing the hazard lights for a railroad crossing.

One driver offered to take a bandmate the rest of the way to Marion. They didn’t hear from him for the rest of the night. Another passing motorist drove another bandmate to Marion, too. But by that time the remaining members of Effic had found that they could get the bus going again if they pushed it into motion under their own manpower.

That incident made news, if only because a local reporter was traveling with Effic that night. The scribe couldn’t pass up the chance to write about being stranded in the fog, late at night, in rural southern Illinois.

A roadie later destroyed the bus one day driving back south from a concert in Chicago. He slammed into a hole in the highway that roadworkers had left uncovered.

The bus didn’t last, but Dan still has the guitar he bought in 1975, the year he left the band. “I got tired of partying, I guess,” he said. “I wanted to settle down.”

‘I loved going to work’

Dan joined The Korte Company in 1979 as one of two new carpenter foremen. The first project he tackled was a condominium development in Highland.

He nailed it—no pun intended. In fact, he nailed everything he touched. After a year with the company he became a supervisor, and had set an ambitious trajectory for himself.

“I told Ralph one day that after one year, I wanted to run a $1 million job, and after five years, a $5 million job, and then ten years, $10 million and so on,” Dan said.

As it turned out, Dan beat his own projection, running an $84 million project in 2009.

Dan credits his work ethic and The Korte Company’s culture for the success he enjoyed over nearly four decades.

“It’s a team-building company,” he said.

He recalls the annual superintendents steak fry—a simple affair, just red meat, cold beer and cards at Ralph’s house. And the Halloween hay rides and campfires, and the annual Christmas parties.

“We did off work what we did on a jobsite—we built a team,” Dan said. “I loved going to work. My whole career, 37 years, I looked forward to going to work every day.”

Conducting the orchestra

Dan’s seen his fair share of unique construction projects in his years as a supervisor.

As site superintendent for the Gateway International Raceway in Madison, Illinois, he oversaw construction of the actual racetrack surface as well as anything else that required pavement. He recalls the trips he had to take to Miami to talk to a concrete supplier who developed a special additive that cured concrete faster.

“We worked seven days a week much of the time on that job, and sometimes worked until midnight every night,” Dan said. “We needed so much concrete that we kept the local concrete plants open on weekends.”

Another job was the Wehrenberg movie theater in O’Fallon, Illinois—the first stadium seating theater in the St. Louis metro area. “We had to build from the top down because once you build the concrete risers, you couldn’t get to the ceilings,” Dan said.

They built in reverse order, saving the risers for the end. Workers pumped countless tons of concrete through big hoses that snaked through the theater’s finished lobby.

As the self-made in-house Tilt-Up expert, Dan also supervised two of The Korte Company’s largest Tilt-Up concrete panel structures—the Hershey Midwest Distribution Center and the ProLogis-Unilever Distribution Center—both located at the Gateway Commerce Center in Edwardsville, Illinois.

The 1.26 million-square-foot Unilever building was made up of 505 Tilt-Up concrete panels that Dan’s crews hoisted into place in just two weeks. At the time it was built, it was the largest single-story Tilt-Up structure in the U.S.

The Hershey Midwest Distribution Center initially totaled 1.1 million square feet of specialty sandwich panel Tilt-Up construction. Dan and his teams finished that project so fast, Hershey’s top brass thanked them by flying them out to Pennsylvania for a banquet.

(Hershey called on us again in 2019 to tack on another 292,000 square feet to the facility. Learn about the addition here.)

The Hard Rock Café project in St. Louis was particularly challenging for Dan and his teams. In just 70 days, crews built the café inside what had been the arched-roof train platforms of Union Station. The confined space and tight deadline set the stage for a frantic sprint to the finish: crews worked around the clock for the last week and a half of the job, installing three separate utility services in the same trench at the same time.

But Dan’s proudest moment came shortly after The Korte Company’s expansion into the Las Vegas market.

It was mid-2005, and Las Vegas Division President Greg Korte was in hot pursuit of a retail development project he wanted badly. The owner, American Nevada Company, ultimately agreed to work with The Korte Company on the condition, according to Dan, that they have “someone running the job who had been with Korte a long time and had some gray hair.”

“So I flew out there for an interview, and I hit it off with the owner,” Dan said.

Soon after Dan returned to Vegas to run the job, teams were perilously behind schedule. The owner told Dan he’d never finish on time.

“I dug my feet in, did what I could,” Dan said. They did finish on time. “After that, the owner’s representative said that they wanted me on any new job they started.”

So how did he do it? How did Dan Scott, the lead guitarist of Effic and the hardworking grandson of the best cabinet maker in town, make such a mark on jobs across the country?

He treated every job as if it were a symphony and considered himself the conductor.

“When you watch an orchestra, the musicians don’t all start playing at the same time,” Dan explained. “Sometimes the beauty of the music isn’t the notes you hear, but the placement of the empty spaces between notes.”

And just as a conductor knows his musicians, Dan knew his crews.

“You treat everybody fair,” he said. “I always had regular meetings with project managers and foremen. But on the site, I’d talk baseball with the low guy. You work them from the top and from the bottom.”

“It’s a team. You need to build relationships,” Dan added. “Knowing how the thing is supposed to go is only half of it. Getting people to cooperate is the other half.”

‘All waking hours’

Today, Dan’s symphony is his garden.

A cut flower plot he recently created fuels his wife Susan’s passion for creating floral arrangements. Harvests of fruits and vegetables go straight to a semi-professional home kitchen. Susan’s mastery there keeps them well-fed.

“She’s my anchor through all this,” Dan said of Susan. They just celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary.

And the band is getting back together. Effic is working itself back into show shape in anticipation of a reunion this year.

“We will be set up this fall hopefully,” Dan said. “We practice all waking hours over three-day weekends. Our bassist flies in from Houston and the rhythm guitarist comes in from Dallas.”

Rare among rock and roll bands from the 70s, all of Effic’s original members are still alive and healthy.

And if all goes to plan, Dan Scott—the conductor—will take the stage again.