“I’m tearing down a porch outside, and I’ve got some people working out there so we’ll just get it done and I’ll go back out.”

As Rich settles in for a conversation about his 38-year career as a superintendent at The Korte Company, it’s clear his days of leading projects and working with people are far from over.

Right away, he’s cracking jokes about how he won’t remember dates of the many university, hospital and public facilities he’s built. Also, what appears to be a zebra hide is hanging on the couch behind him—more on that later. But Rich does remember the people: the mentors who took him in under their wing, the jobsite camaraderie, the friendships forged even with hard-to-please owners.

The Korte Company builds structures, and Rich has left his mark on hundreds of them. But it builds relationships, too—and in that endeavor, Rich was one of the best.

Third baseman for “Cousins, Brothers and Others”

Rich grew up in southern Illinois—raised in a small township called Old Ripley, then moved back to Highland where he was born—with a carpenter father and a mother who soldered components at Basler Electric. In the country, potential projects were never far away.

“You were either out on a tractor or making hay, feeding hogs, feeding cattle, planting whatever it was. That’d keep you busy in the spring and then until school started again. Then you just worked on weekends and after.”

A stint building ponds for Weder’s Camp and Fish, a local camping area, gave Rich experience operating heavy machinery at just 17 years old.

In his leisure time, fishing, swimming and biking were the go-to activities for Rich. He also played on a local softball team with other kids his age. This was before competitive select teams took over youth sports, holding extensive tryouts and traveling for tournaments every other weekend. This was just a group of local kids playing ball. Incidentally, majority of the players were part of the Korte family, hence the group’s clever name:

“Our team was called ‘Cousins, Brothers and Others.’ I was the other.”

Rich shined at third base, flashing leather in the notorious infield “hot corner.” He played alongside teammates and classmates like Gary Korte (a future EVP of The Korte Company). And in just a few years, some of these teammates would become coworkers.

“‘Big Toe’ took me under his wing”

Rich entered the workforce immediately following high school. One day after graduation, to be exact.

“My father said, ‘If you’re not going to college, you’re getting a job.’ He knew I’d get into trouble.”

He started out at Lindsey Construction, where Rich built fast-food restaurants all around the country. It was a learning experience where he did “a little bit of everything.” But Rich learned fast—fast enough to start overseeing jobs.

“I started running work when I was 19 years old. That was pretty unusual at the time because young kids don’t get any respect. And respect comes from, I hate to say it, age. But it also comes from your knowledge. If you can show them that you do know what you’re doing, then it’ll come.”

While he didn’t have the age yet, Rich had the knowledge. The restaurants were practically identical from one to the other: same materials, same subcontractors, same timeframes. This made for an ideal training ground for Rich to build his skill set and also get his feet wet on superintendent work.

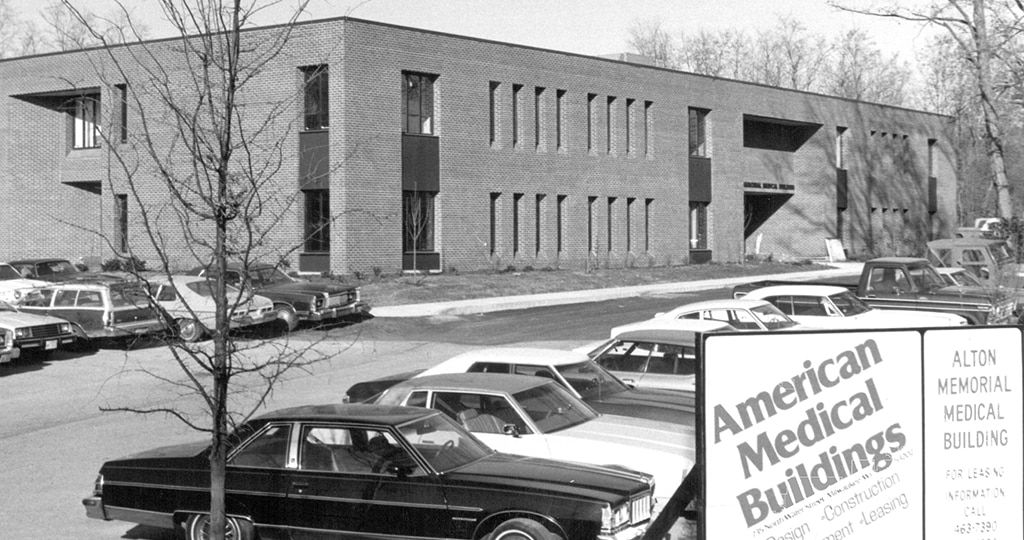

After putting in seven years at Lindsey Construction, The Korte Company hired Rich as a carpenter in November 1979. His first job was at Alton Memorial Hospital, a level up from his previous work: all the other projects he’d done had been single-story stick-built, and this was a multistory building on a large medical campus.

Thankfully, he had a guide—Jerry Deininger, the superintendent on the job.

“Jerry was very knowledgeable and kind of took me under his wing and taught me a lot of stuff. His nickname was ‘Big Toe.’”

This moniker was used (informally) at The Korte Company. It designated a superintendent who’d been everywhere, knew what to do next and knew how to drive the job. Jerry passed this knowledge onto Rich.

“I learned how to read different types of blueprints and got to understand how to run work. You’ve got to be there earlier than anybody else and have the day planned out and make sure you have your subs in line. He made me plan.”

Jerry’s next project was a multi-million dollar gasification plant in Alton, Illinois, right next to the Mississippi River. He chose Rich to be one of his foremen. One more project later and Rich was promoted to superintendent for The Korte Company.

The role takes on a lot of responsibility, with everyone on the project answering to the superintendent. Rich acted as the direct contact for owners and master scheduler for all the trades (making sure flooring crews weren’t scheduled on top of plumbing subs, for instance). He knew when to push—“If you can get it done sooner, Ralph makes more money”—and when to listen to his coworkers on the ground.

“The people that knew what was going on in a job were the foremen. The owners were there, and they would say more or less, ‘Yes, we can do it.’ And the foremen go, ‘No, we can’t. Not with the manpower.’ So then you get them in a meeting, and everybody gets together and works it out.”

Each job posed its own challenges. When building a USPS Mail Processing Facility in Richmond, Virginia, Rich had to oversee trades, schedules and quality on a 719,000-square-foot facility—that’s 16 acres of the building footprint alone. They had to move around the jobsite not on foot, but on golf carts and ATVs.

A second-floor addition to the Women’s Pavilion at Anderson Hospital included 17 post-partum/delivery rooms, a nursery, a social servile suite, a classroom, a waiting room and a staff office suite. Construction also took place while the first-floor OB unit was fully occupied.

“They were still having babies below us. We had a meeting with the head nurse and I said, ‘I’ve got to jackhammer up the floor and we’ll try and be as quiet as we can.’ She looked at me and she says, ‘You wake ‘em, you rock ‘em.’”

Despite the constraints, both labor units operated without disruption (and Rich didn’t need to rock any babies back to sleep).

But his most challenging job also ended up being his most rewarding, where the validity of an Olympic record was on the line.

Going for the gold

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville had hired The Korte Company to build their track, field and soccer stadium. The venue also needed to meet Olympic Committee standards, as it was going to be a venue for the 1994 Olympic Festival.

The now-bygone event brought together amateur, rising and professional athletes across winter and summer Olympic sports. Jackie Joyner-Kersee, a native of nearby East St. Louis who by then was already a six-time Olympic medalist, was expected to set a new record at the event. (She broke her own world record in the heptathlon at the 1986 Olympic Festival) But for it to count, the facility measurements had to be nothing short of perfect.

“When I built it, I had to keep everything within tolerances, and everything went from inches to centimeters and meters instead of inches and feet and yards. I had to get a different outlook on everything.”

So if Joyner-Kersee broke the record but Rich’s work was imperfect, it wouldn’t count.

Knowing the stakes, Rich and his team set out aiming only for perfection; going for the gold, if you will. They built the shot put, javelin and two dual-directional long and triple jump areas. They laid out the track down to the exact degree. And when the Olympic Committee reviewed their work on the 3,000-spectator stadium, it passed.

Joyner-Kersee easily won the 100-meter hurdles and set a U.S. record at 12.69 seconds. Rich and his team won the Concrete Council Award for the job, and today the venue is named Korte Stadium.

Safari adventures

Rich has always been an outdoorsman, familiar with Missouri and Illinois fishing hotspots like Governor Bond Lake, Meramec Springs and Montauk State Park. So when a friend of his brought up the chance to visit Africa for a two-and-a-half week hunting and camping safari, Rich was immediately on board to go and expand his outdoor horizons.

After a 24-hour plane ride and a 3-and-a-half-hour drive, they finally arrived at his friend’s brother’s home, who still lived in Zimbabwe.

“I was about dead the first day.”

From there, they set out on a variety of excursions. Rich tried out photography skills, and at night they camped in five-star tents with incredible proximity to the local wildlife.

“You woke up in the morning, you took a shower outside and elephants are right next to you, not too far away at the watering hole.”

They took a Jeep out to explore nearby habitats, where cheetahs and giraffes ran right alongside them. For the hunting portion of the trip, Rich got the chance to hunt zebras, impalas, baboons, elands and kudus (two types of antelope), several types of small cats and even hyenas.

The crown jewel of the trip was a sightseeing expedition to Victoria Falls, one of the largest waterfalls in the world. It’s approximately twice as wide and twice as deep as Niagara Falls, and spans the entire breadth of Zambezi River, making it less of a chute and more of a towering curtain of cascading water. Rich saw it up-close and personal.

“I took the boat ride down and was able to walk right up to it. Then we took a helicopter ride over the top of it, which was really impressive.”

Rich “learned a lot” in those few weeks, and he brought home a zebra hide as his trophy from the trip. It’s still displayed above the couch in his living room, reminding him of the adventures.

“You just click with some people”

Nowadays he keeps the hunting, fishing and camping expeditions a little closer to home—and with five grandchildren in tow. Rich, his wife Deborah and the grandkids “do everything together” and frequent their lake house at Governor Bond Lake.

“It’s a nice lake and it’s not too crowded. The grandkids like to go tubing; we fish in the morning and tube in the afternoon so everybody’s happy.”

After working for The Korte Company for nearly four decades, almost all of which he spent as a superintendent, Rich retired at the beginning of 2017.

“I just appreciate them giving me a chance at the beginning. I had some experience and they let me expand on everything I had.”

In retirement, the first thing he missed was the camaraderie.

“I’ve met a lot of friends not only with The Korte Company, but also friends working on the job. Especially Anderson Hospital, Dan and Bill, I still talk to them. I mean, I bet I’ve done 10 jobs at Anderson and they were very good to work with. Very strict, but very good people to work with. And subs and carpenters and electricians or anybody. You just click with some people.”

He remembers working on a condo development in Marco Island, Florida and the chance to get some elbow-to-elbow time with Ralph Korte. They went to Stan’s at Buzzard Bay, a “millionaires to biker bar that’s just like a Fast Eddie’s on the water.”

Old ‘70s and ‘80s music blasted through the speakers as the two took the time to just chat after a long day on the jobsite.

“I had a great time. That was fun. You don’t get to go out and hang out with your boss too much.”

He’ll still pop into the office to “aggravate everybody once in a while,” grabbing coffee and catching up with old friends. But aside from that he’s full-on retired, save for the bathroom remodels and odds-and-ends projects his nephews will recruit him for. And there’s the porch he’s tearing down today.

“I’ve got guys out there. They’re probably going, ‘Where is that lazy son of a gun now?’ I bet it wasn’t son of a gun either.”

And just like that, he’s back to building.