Motorists turning off Illinois Route 158 toward the main entrance at Scott Air Force Base wouldn’t see the Scott Club right away.

It’s past base housing, past a couple small shopping plazas and past the visitor center with its view of a half-dozen retired aircraft parked for good on big circular pads.

Then, off to your right, about a mile from the interchange and just before you pass through security, you see its brick façade and concrete accents and tall, dark windows.

It’s a striking building. It’s certainly imposing. It might even be beautiful.

And it’s there because of Design-Build.

‘That’s not what Design-Build is about’

By the time the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers tapped The Korte Company to build the new club, the industry’s perception of Design-Build had changed.

What had been unthinkable in the late 1970s and an outcast method throughout the 1980s had, by the mid-1990s, become an accepted construction delivery system. No less than the federal government had given its seal approval.

The Corps was clear that the Scott project would be Design-Build. They released dozens of full-size drawings that specified a two-story structure featuring exterior design features bearing a resemblance to other buildings on-base.

“But there were some things missing in the drawings,” said Dennis Calvert, then a vice president of marketing. “There was no heating system. No structural information.”

Nonetheless, we and a handful of competing Design-Build firms submitted initial proposals. But none of the bids could meet the Corps’ budget of $8.3 million, including our own, which stood at around $9.7 million.

Dennis recalled: “I learned that the Corps had hired an architect from Cincinnati to do this project and they were around 90% complete with their documents when the estimates started coming in $2 million or $3 million over their budget.”

Dennis also learned the work was not initially meant to be Design-Build. But seeing the persistently high estimates, the Corps released the documents anyway and signaled that the project would be Design-Build in hopes that that would bring the cost down.

“But that’s not what Design-Build is about,” Dennis said. “You can’t just do all the things you used to do (in traditional design-bid-build delivery) and expect the price to change.”

Later, the Corps adopted a more flexible stance. How close could we come to those original designs without exceeding their $8.3 million budget?

That’s where the problem-solving kicked in.

Cutting $1.5 million off the top — literally

The Scott Club actually is two clubs combined: Officers have one end of the building and enlisted airmen have the other. The space shares a main ballroom; the kitchen and other facility support systems also serve both sides of the club.

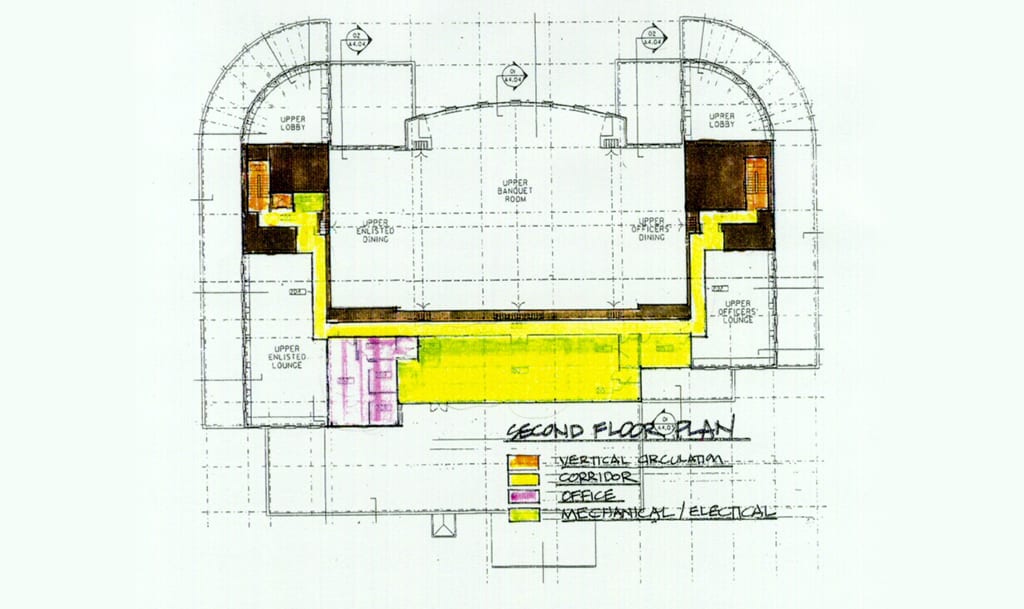

The Corps’ original drawings proposed a 6,000-square-foot second story with some offices, storage space, a large mechanical room and a balcony where people could look down onto the ballroom. Two stairways and two elevators — one of each at each end of the club — would provide access to the second floor. A third stairway in the rear of the building would serve as a fire exit.

But our Design-Build team targeted what they believed were weaknesses in the design that was provided in the Corps’ request for proposals (RFP).

First, the amount of usable office space on the second floor only amounted to 1,000 square feet. The mechanical room took up much of the rest of the space, but it was in a relatively inaccessible location that would make it quite difficult to position and install replacement equipment.

Second, code requirements stated the balcony needed to be fire-protected. Instead of peering down into the ballroom, anyone on the balcony would peer straight into a two-hour firewall.

A third challenge revolved around the structural bones of the facility. Initial drawings showed inconsistent bay spacing with load-supporting columns at unequal intervals. If the club was built as initially proposed, this could have resulted in beams, purloins and roof decking needing to be custom-fabricated to various dimensions, and that contributed to bidders’ higher price tags.

Was a 6,000-square-foot upper floor containing only a couple of offices, a mechanical room and a useless balcony worth the cost? Was the inconsistent bay spacing worth the material and construction headaches that would result?

Our design team proposed four major changes that fundamentally shifted the course of the project:

First, the mechanical systems would sit on the roof instead of inside the building. Obscured by aspects of the roof, they would remain invisible from the circle drive that wraps around the building.

Second, the upstairs offices were moved downstairs because there was plenty of room for them there.

Third, there was also plenty of room for storage on the ground floor as it was, so we removed the second floor storage space entirely.

Fourth, the bay spacing was adjusted for symmetry. It dramatically simplified the project’s material and construction requirements.

“But we left some of the height of the building, cutting its height only by about eight feet,” Dennis said. “We eliminated the two elevators, the two sets of stairs and that entire second floor.”

The design changes brought the plans into alignment with one of Dennis’s pro tips to architects: It’s always easier to design around a sound structural system than it is to force-fit a structural system into your design.

“The Corps was at $8.3 million. We got it down to $8.2 million and some change. And, we gave them a better building,” Dennis said.

An award-winning facility’s one change order

To learn if the changes were enough to get the Corps on board, Dennis would need to make a presentation to regional authorities in Louisville, Kentucky.

The presentation included a scale model of the facility and even a graph illustrating the improved performance of an HVAC system we proposed as an alternative to what the Corps had specified.

“We made a spectacular presentation,” Dennis said. “They ate it up.”

We won the job.

And what a job it was: Its completion in July of 1997 was a staggering six months ahead of schedule.

The Construction News & Review, the Construction Industry Institute and the Design-Build Institute of America all recognized the facility.

The Air Force did too, choosing the building as its winner for that year’s Design Award. Finally, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers presented The Korte Company with its Medallion of Excellence in recognition of a job very well done.

It would have been the perfect project if not for one change order at the very end.

“Initially we were going to plant grass seed around the building,” Dennis said. “But four or five generals were traveling from here, there and yonder for the opening ceremony so they changed it from seed to sod.”

Easy enough.

Almost 25 years later, the building still looks magnificent.

So does the grass.